It’s coming up to six months as a HEMS Paramedic with the Devon Air Ambulance! Time moves quickly and the learning curve has been steep. I have attended a variety of incidents; all challenging in different ways and thought I would share my personal checklist that I go through before, and at key points during missions.

This is my personal list of tasks that I have developed from my experiences over the last six months. I generally go through this en route to an incident when sat in the rear of the aircraft with no other immediate tasks to perform. It is intended to lessen the mental pressure or ‘cognitive load’ that comes when getting ready to arrive at a serious incident, and avoid tasks being overlooked or missed.

In the aviation world such an error would be called a ‘human factors incident’. Aviation is well known for its use of checklists to reduce human errors and the medical world has incorporated similar practices in areas such as surgery and some ED practices. For me this list is just to help me turn up at an incident and make things run smoothly without any errors – the goal is to ace every job! We can’t always achieve this but you have to start with that intention, and this list is part of that intention.

In the aviation world such an error would be called a ‘human factors incident’. Aviation is well known for its use of checklists to reduce human errors and the medical world has incorporated similar practices in areas such as surgery and some ED practices. For me this list is just to help me turn up at an incident and make things run smoothly without any errors – the goal is to ace every job! We can’t always achieve this but you have to start with that intention, and this list is part of that intention.

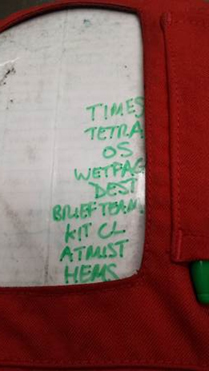

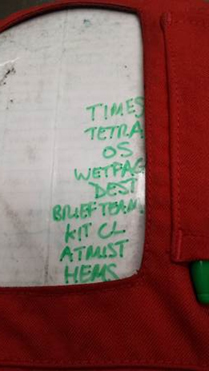

So let me take you through the scribbles…

TIMES: Start by writing down the time the incident took place, time we took off, the time the helicopter arrived etc, sounds simple but can be easily overlooked when trying to get updates on the patient condition and getting kit ready to leave the aircraft. These times can be important when building a picture of events later and when answering questions posed by the doctors at hospital as it may inform their decision making. These times can be gained from control but are better if they are in your hand when someone wants an answer.

TETRA: This is the type of radio in the aircraft we use to communicate with control. It allows us to send our status i.e. ‘arrived at scene’ without having to speak to them, this both saves time and lets them know where we are.

OS: Stands for ‘Ordinance Survey’. Get the map for the area of the incident and mark the target in pencil, pass it forward to the paramedic in the front of the aircraft. They are working the electronic navigation aids but need this as a back-up and quick reference. The landing site can then start to be planned (a location such as a forest means we need to look at the nearest practical site, and there are lots of other issues to consider with landing sites)

WETFAG: This is something we do when attending incidents with children. WETFAG stands for Weight, Electrics (in the form of the number of joules required to deliver a de-fibrillating shock to a child in cardiac arrest), Tube (size of tube used to secure the airway), Fluid (a weight adjusted IV dose), Adrenaline/Amiodarone (drugs we give in cardiac arrest), Glucose (again an IV dose).

All of the previous are adjusted to the age and suspected weight of a child and given the emotional pressure that can come with paediatric incidents it is clearly helpful to have these values prepared and visible in advance. When I do this I remind myself to check the age given is accurate when I arrive on scene.

DEST: The Destination gives us an idea what is wrong with the patient and which hospital is going to be most appropriate for them. The joys of a helicopter mean we can take patients to specialist centres that give the patient the best chance of recovery. Sometimes the weather has other ideas so we need to know our options and plan around them, it is always better to do this early.

BRIEF TEAM: I may know what I intend to do with the patient but the others can’t read minds!

We work closely with the ground emergency ambulances and generally attend incidents together. Covering the whole of Devon and beyond means we work with a lot of great different crews. If the patient is going to travel in the aircraft then it is up to the HEMS crew to take responsibility for their care during the flight. That means getting them packed suitably for the aircraft with any essential interventions performed ideally before take-off (noise and space makes certain things more challenging in flight). Making sure that happens requires effective team-work, a team can only function once they know the tasks they need to perform so I endeavour to state what needs to be done and organise who is going to do it. Getting peoples first names helps this process run smoothly. I am regularly impressed by the way ambulance staff that have never worked together suddenly become an effective team and get numerous tasks done in rapid fashion. Sometimes the care on scene has been so thorough that there is little more that needs to be done.

KIT CL(Check List): This is the last check we carry out as the patient is placed in the aircraft and ensures that the medical equipment/drugs we may need during flight are placed close to hand. A printed sheet in the back of the aircraft needs to be looked at and read so we know the essentials are there. It only takes seconds.

ATMIST: Another check list within a list! Our method of pre-alerting the hospital we are taking the patient to with the relevant information (Age, Time of incident, Mechanism of injury, Injuries found, Signs & Symptoms, Treatment given). I like to do this whilst the rest of the assembled team is loading the patient in the aircraft, away from the incident if possible in my own ‘sterile’ environment, so this can be passed clearly, quickly and without interruption (not forgetting to let them know the patient is coming by aircraft! Please meet us at the Helipad!)

HEMS: Last but not least, our dedicated HEMS controller needs contacting. There are a number of Air Ambulances that operate in our ambulance service, sometimes we want to go to the same hospital at the same time, so we need to know that our intended helipad is clear or if we need to start forming plan B.

So there are lots of things to consider and the checklist acts a visual reminder so as not to miss anything when the pressure is on!

That’s rather a long blog for a short list but I hope it was of interest!

Catch you next time!